The Meiji period (1868–1912) contained many aspects of Japanese culture and customs that are still relevant today

![]()

![]()

事務局からのお知らせ

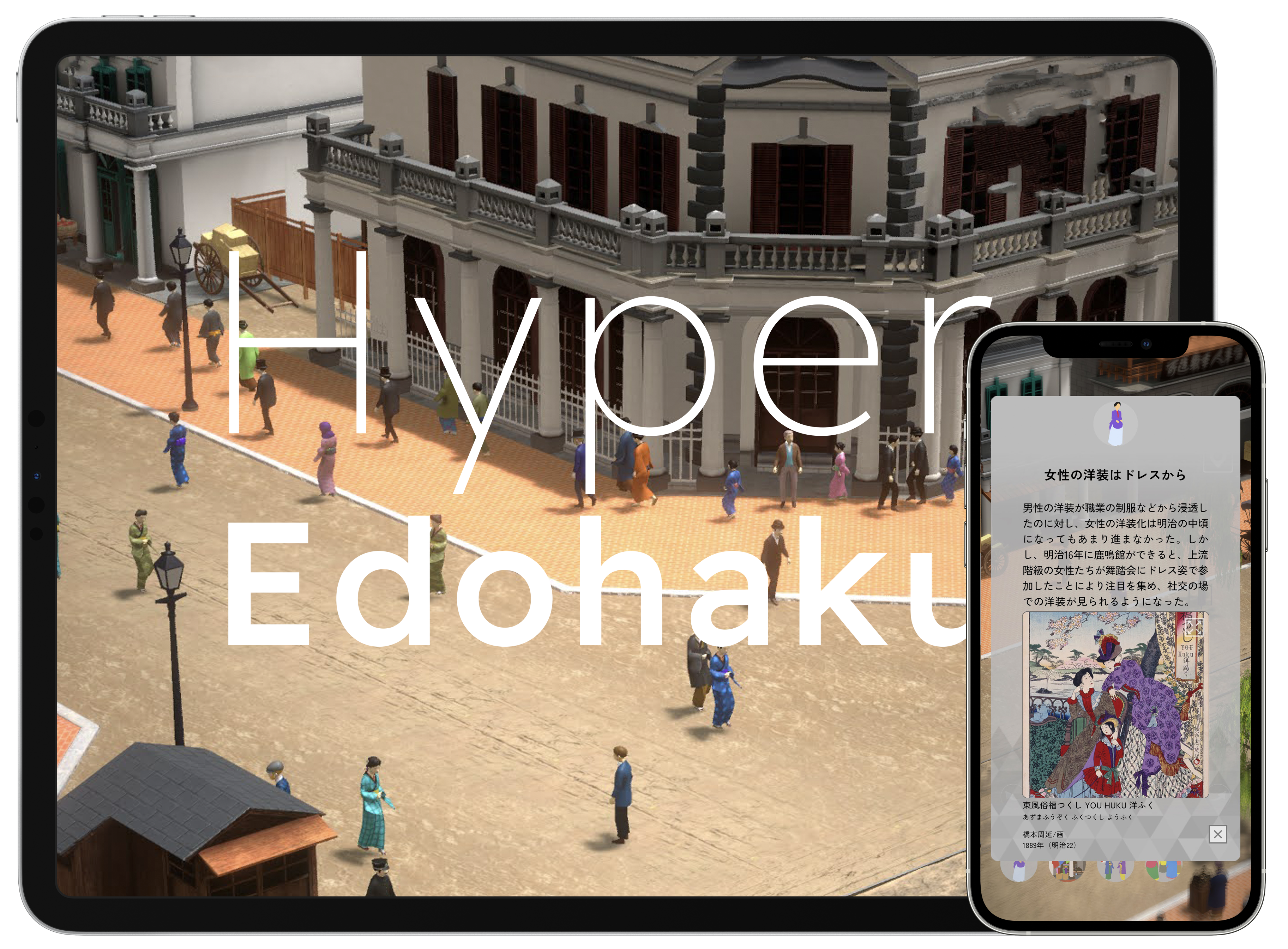

Journey Back in Time to Ginza during the Meiji Period to Discover the Birth of Modern Tokyo! Now Available: “Hyper Edohaku Ginza: From Edo to Tokyo,” the Latest Version of the Edo-Tokyo Museum’s Smartphone App

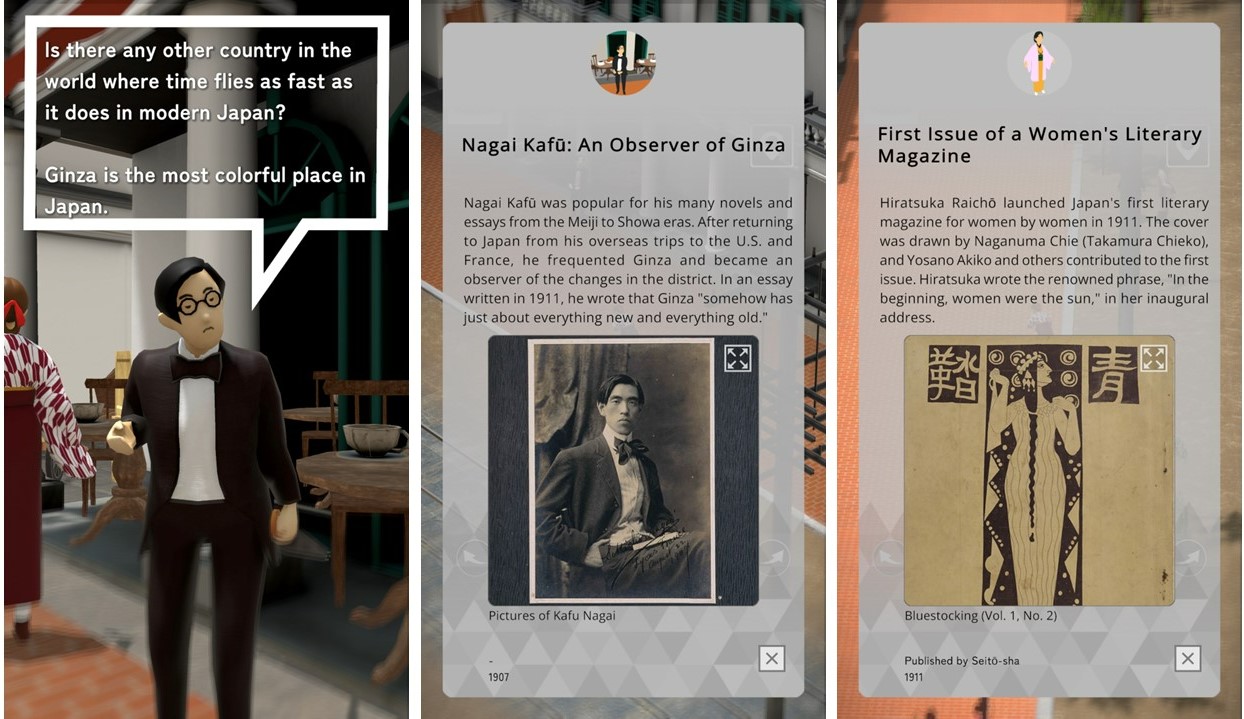

The theme of the newly-released Meiji Ginza Edition is “Journey Back in Time to the Birth of Modern Tokyo.” In the app, users stroll through the streets of Ginza during the Meiji period while searching for 100 items selected from the Edo-Tokyo Museum collection of approximately 350,000 items . Why was Ginza during the Meiji period specifically chosen for this new edition?

Kutsusawa: First of all, one of the reasons we chose Ginza was because we have a model of Ginza Bricktown in the museum. As for why we chose the Meiji period, just as the 150th anniversary of the opening of Japan’s first railway became a hot topic last year, many institutions and aspects of Japanese culture that are still relevant today began right around 150 years ago during the Meiji period. These include the postal system and our modern currency based on the yen (1871), our educational system (1872), and the adoption of the Gregorian solar calendar and the fixed 24-hour day (1873).

Ginza underwent a drastic transformation after the great fire of 1872. The Meiji government pushed for the creation of a fire-resistant city, and Ginza Bricktown, with its Western-style streetscape, was built at that time. In 1895, the first clock tower of the K. Hattori Clock Store (now WAKO in SEIKO HOUSE GINZA), a familiar landmark to most Japanese people, was completed. People’s lifestyles also began to change with the introduction of Western-style clothing, Western-style dishes such as curry, and modern, trendy foods (at the time) such as ice cream and ramune soda.

Ginza during the Meiji period seemed to be the perfect setting to learn about the time period and discover the birth of these aspects of modern Japanese society.

Time travel through four decades to experience the progression of time in a realistic manner

Unlike the previous Edo Ryogoku Edition, whose entire story takes place on the day of the annual Sumida River Fireworks Festival, this edition divides the 45 years of the Meiji period into four decades and comprises four stages. The story of a family that lived during the “civilization and enlightenment” of the Meiji period unfolds against the backdrop of these various societal transitions.

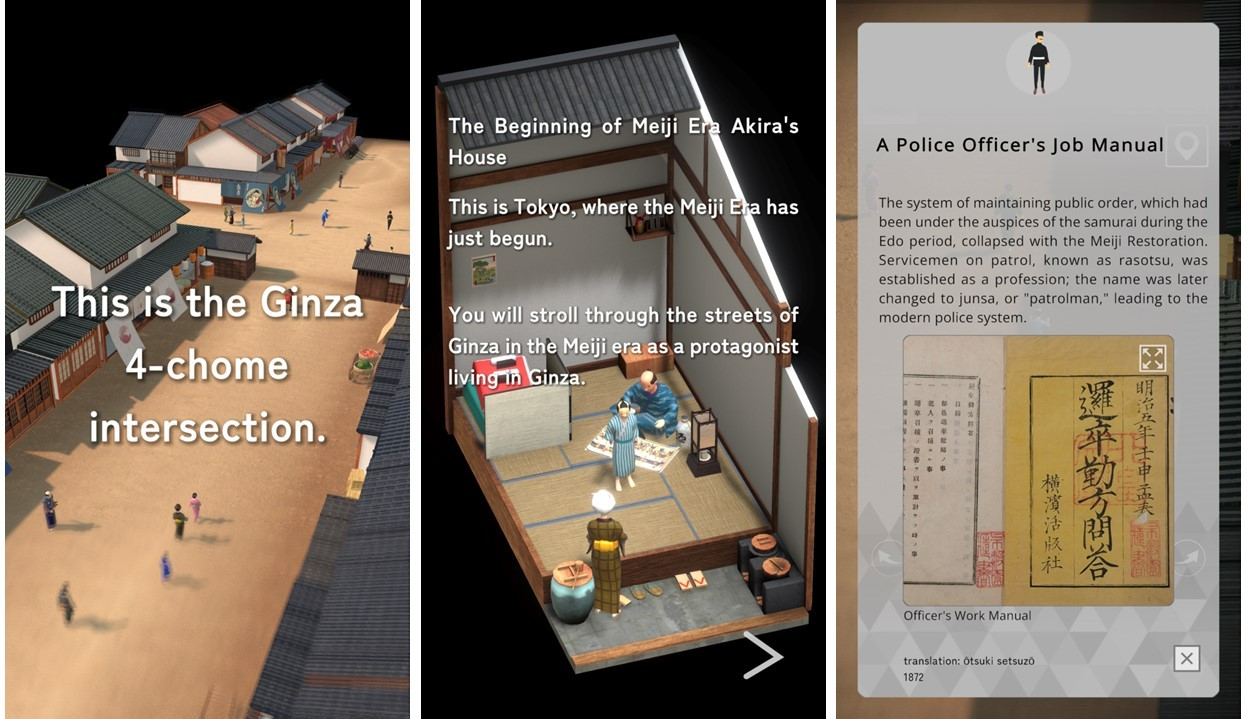

Upon launching the app, users are whisked back in time to Ginza at the beginning of the Meiji period (circa 1868), when Edo was renamed “Tokyo.” Controlling the avatar of Akira, a young boy who lives in a nagaya (row house) with his parents, they will search for items in the museum collection related to various institutions that began in the early Meiji period, such as the post office and police system, while exploring Ginza, a district that still retains strong traces of the Edo period.

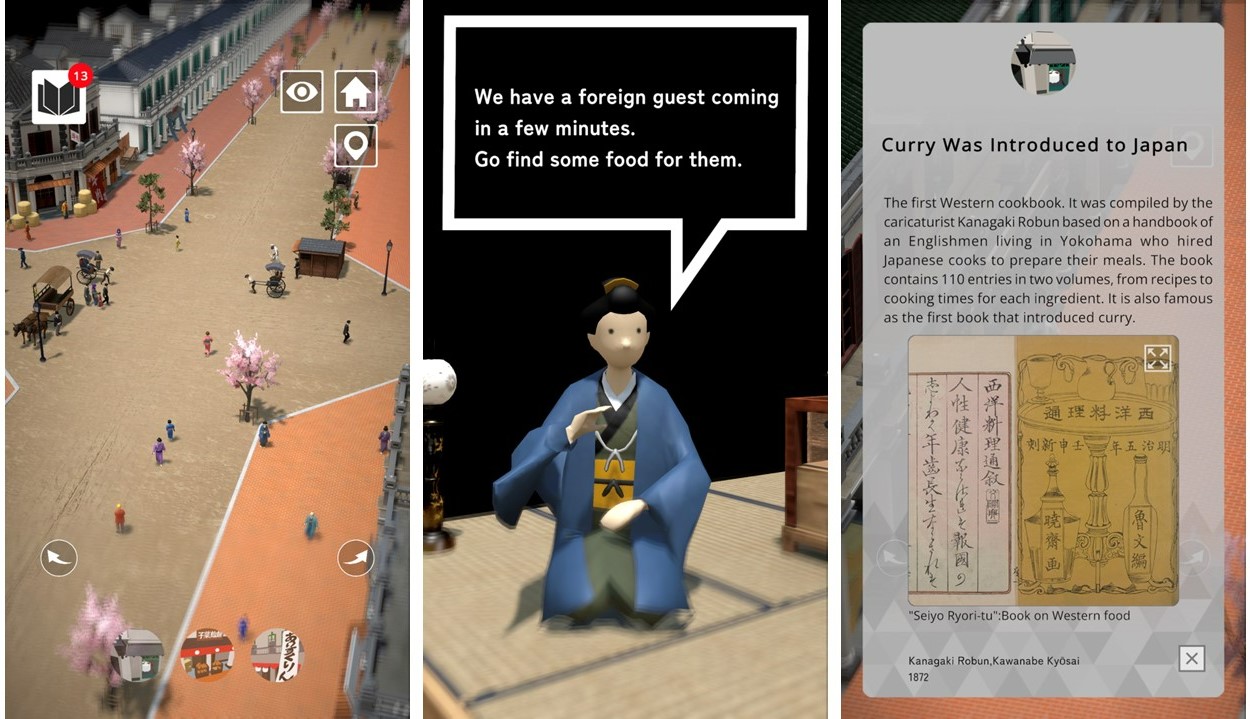

In the next stage, circa 1877, Akira’s childhood friend Haru collects trendy food items for international visitors and investigates the latest vehicles in Ginza, where swanky brick buildings now line both sides of a spacious avenue.

In the third stage, circa 1887, Westernization is advancing, and Ginza has become a center of commerce and communication in Tokyo. Akira, who has grown up to be a fine young man and has started working at a newspaper company, a major hub for the dissemination of information at the time, investigates cutting-edge fashion items such as Western-style hats, shoes, and umbrellas, as well as Western music that began to be performed at the time.

Finally, we move on to 1907. Ginza has become a glamorous, high-end commercial district that attracts crowds of visitors, and Akira and Haru have been blessed with a daughter named Gin. Gin meets Nagai Kafu, a Japanese literary figure who frequented Ginza often, and collects materials related to the literature of the time, including those of Natsume Soseki and Hiratsuka Raicho. After clearing all four stages and collecting 60 items, users will be able to enjoy time travel, moving back and forth between the stages as they please.

The idea of “time travel” arose during the production process

The best feature of the Meiji Ginza Edition is being able to realistically experience how Tokyo’s Ginza district rapidly transforms during the Meiji period and how the characters grow over the decades in each of the four stages. Where did the idea of having users “time travel” come from?

Taniguchi: Initially, we planned to make it like the Edo Ryogoku Edition, with all events taking place on a single day in the Meiji period. However, during our meetings, we talked about how modernization did not begin suddenly with the Meiji period, but rather that there was a gradual transition from the Edo to the Meiji period. On the production side of the team, we suggested that the planners try to show that decade-by-decade transition in the app. I think it was a challenge for the Edo-Tokyo Museum, but as we continued to discuss the concept, we came to realize that it was actually easier to create a story this way.

Kutsusawa: In fact, even during the same Meiji period, the streetscapes and people’s lifestyles were completely different during the years closer to the Edo period and the years closer to the Taisho period (1912–1926). For instance, people generally tend to assume that everyone wore Western-style clothing in the Meiji period, but in reality, even at the end of the Meiji period, those who dressed fully in Western-style attire were mainly affluent members of society and men in uniform, while women mostly wore kimonos. Certain articles of Western clothing were introduced at different points in time; for example, at the beginning of the Meiji period, some people wore kimonos over their dress shirts to keep warm, and towards the end of the period, girls could be seen wearing haori and hakama (a traditional Japanese jacket and wide pleated trousers) paired with Western-style boots. Fashion changed tremendously during the 45 years of the Meiji period, and the app reflects these research-based historical details.

Focus on the details: Reproducing Ginza Bricktown

The streetscapes of Ginza 4-chome and 5-chome (gochome), where the story takes place, were created based on 3D scans of the model of Ginza Bricktown in the Edo-Tokyo Museum collection. According to Taniguchi, it was quite a challenge to precisely reproduce the changes that took place in a district that changed so drastically over 45 years.

Taniguchi: It was really difficult to reproduce the city layout while maintaining a sense of consistency throughout the changing decades. We ended up creating it in 100 or 200-or-so segments by combining museum models, photographs, maps, and other materials. That being said, there were definitely people who grew up in that era who experienced those changes firsthand, like the characters Akira and Haru. We tried our best to make the app simulate that firsthand experience for users, but doing so was more difficult than it sounds. Unlike the chaotic streetscape of the Edo RyogokuEdition, the scenery in Ginza Bricktown is made up of similar buildings, and it would have been surprisingly boring if we created it exactly according to the research. So, we added small elements such as more vivid colors and signboards to vary the scenery, while checking each detail with Kutsusawa to ensure that nothing that we added went beyond the scope of their research.

Kutsusawa: From a research perspective, a lot of questions came up while creating the space. Although we had photographic data from the Meiji period, naturally, these photographs only captured the most photogenic parts of the buildings. This led us to ask questions such as, “The front of the building is visible, but what does the back of the building look like? What about the view from the opposite side of this street?” As for the stores in Ginza, while it is relatively easy to find materials on long-established stores that still exist today, tracking down small stores that have no remaining records is another story. In cases like this, we relied on newspapers and advertisements from the time, in addition to photographs, to reconstruct the streetscape.

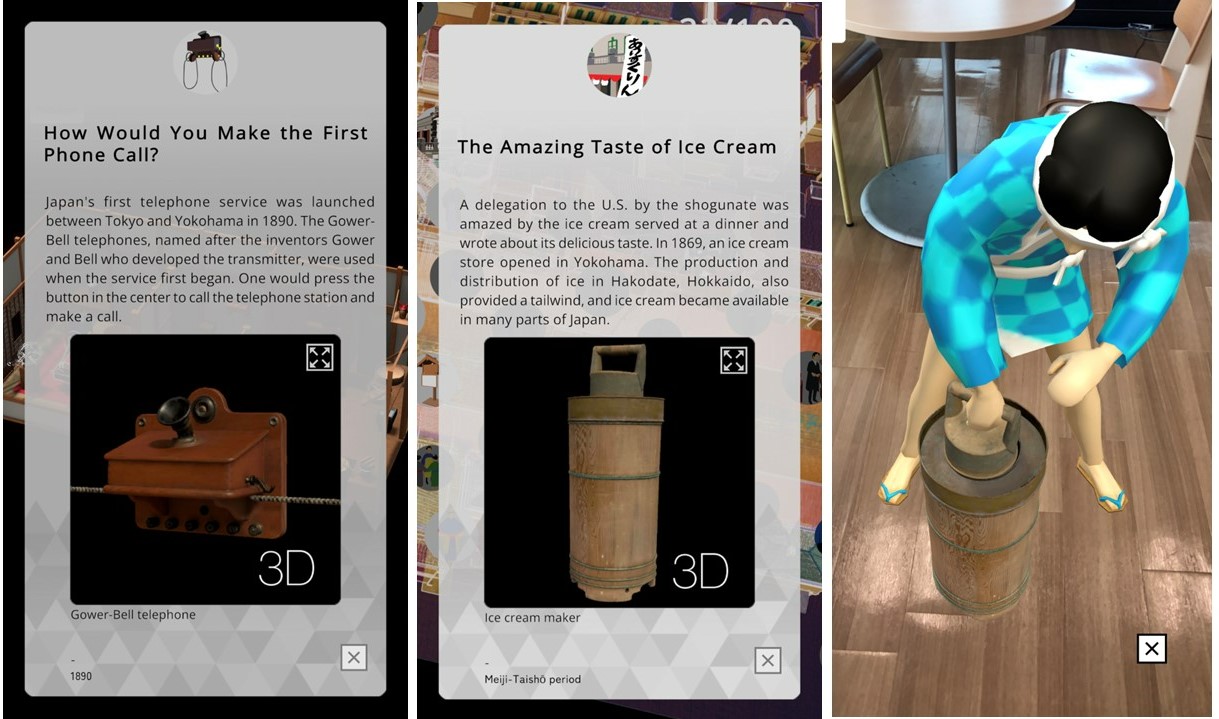

Integrating actual items from the Meiji period in the real world with the AR feature

A new addition to the Meiji Ginza Edition is the Augmented Reality (AR) feature that utilizes 3D data from the museum collection. Using this feature, six of the 100 everyday items from the collection that are hidden in the app can be projected onto the real world. Users can move these items around and view every detail from any angle, allowing them to experience how these items were used at the time.

Kutsusawa: One of the requirements for making a 3D model is that the item must be three-dimensional. Looking at the three-dimensional items we had in the collection, we decided to select six objects that still exist today, but with a slightly different shape or use. For example, a bicycle with a large front wheel and small rear wheel, or an ice cream maker, which is a rare sight nowadays. The app has an AR feature, so users can use their phones to take pictures of the items superimposed on the real world and post the pictures on social media. Personally, I would like users to find the telephone that was used in Japan early on. They’ll be able to appreciate how different these phones are from today’s phones, even though they are the same type of device.

Following the Edo Ryogoku Edition (2022) and the Meiji Ginza Edition (2023), the next edition of Hyper Edohaku will be the Edo Nihonbashi Edition (tentative title), scheduled for release in FY2024. This editionwill be set in Nihonbashi, a district where goods and people flowed back and forth constantly, and themed on the world of commerce in the Edo period. The museum is also considering using the 3D CG space developed for the app as a teaching tool for students of history and in the permanent exhibition at the Edo-Tokyo Museum once it reopens.

Instead of viewing an exhibit from the outside, Hyper Edohaku makes it possible for users to step inside digitally reproduced models of historical spaces and relive the history and culture of the Edo and Meiji periods from within. We hope that you will take this opportunity to download the apps and enjoy a journey back in time, comparing life back then with contemporary life and the city of Tokyo today!

Reporting and text: Setsuko Kitani

Photography: Katsumi Minamoto

Translation: Jena Hayama