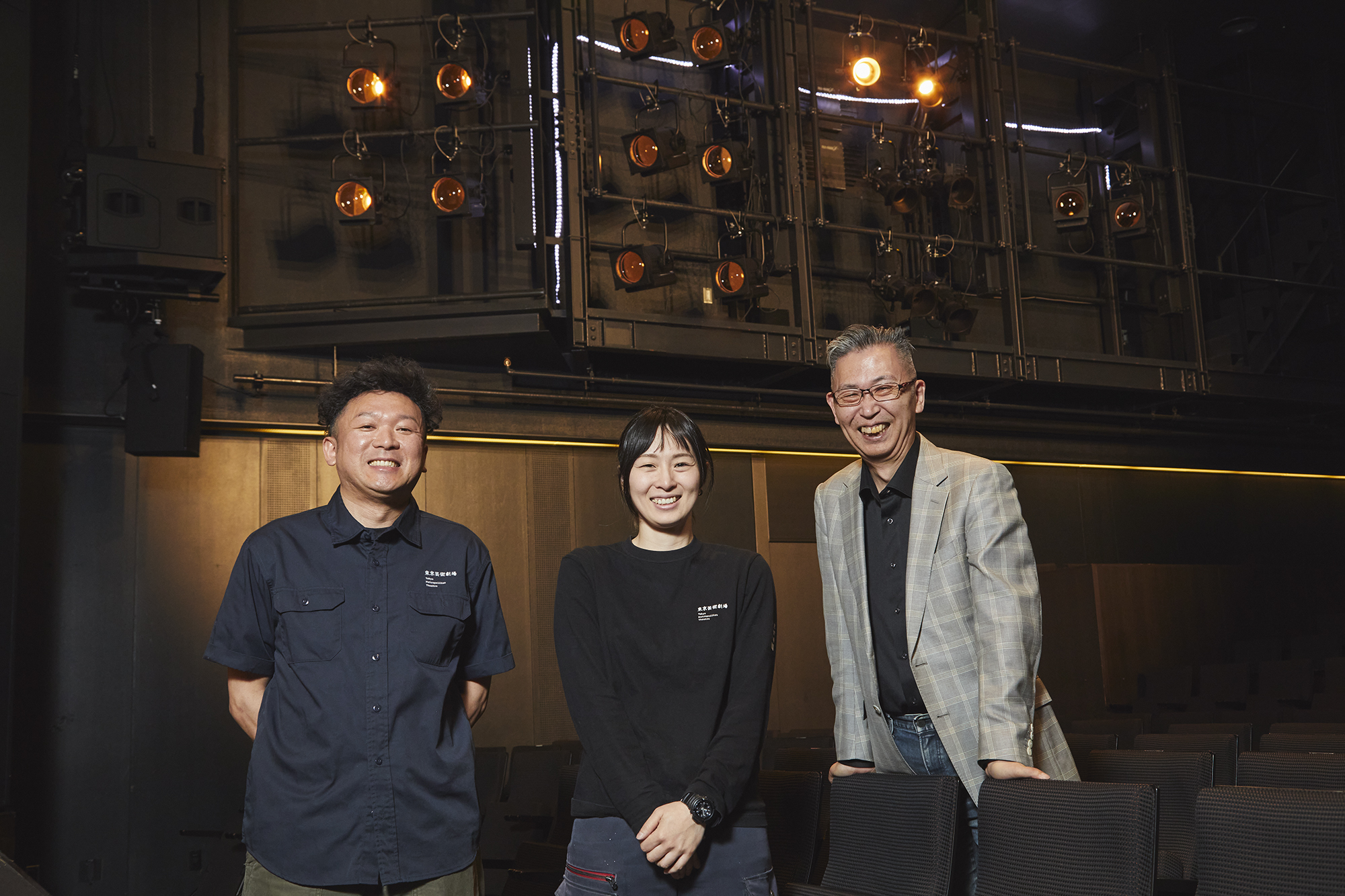

Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture is an organization dedicated to promoting arts and culture through the operation of metropolitan cultural facilities, such as art and science museums, theatres, and halls, and through various Arts Council Tokyo programs. This article series focuses on people working in the foundation to introduce their jobs and personalities. The first edition features three experts in theatre technology at the Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre: Koichi Ishimaru, who is in charge of sound; Keisuke Niijima, lighting and image projection; and Chihiro Matsushima, stage management. We spoke with them about their work, careers, and things they value in their roles.

*Department names and titles are as of the time of the interview

![]()

![]()

事務局からのお知らせ

People Inside Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture Vol. 1: Theatre Technology Professions at Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre [Part 1/2]

Theatre technology professionals who support theatres

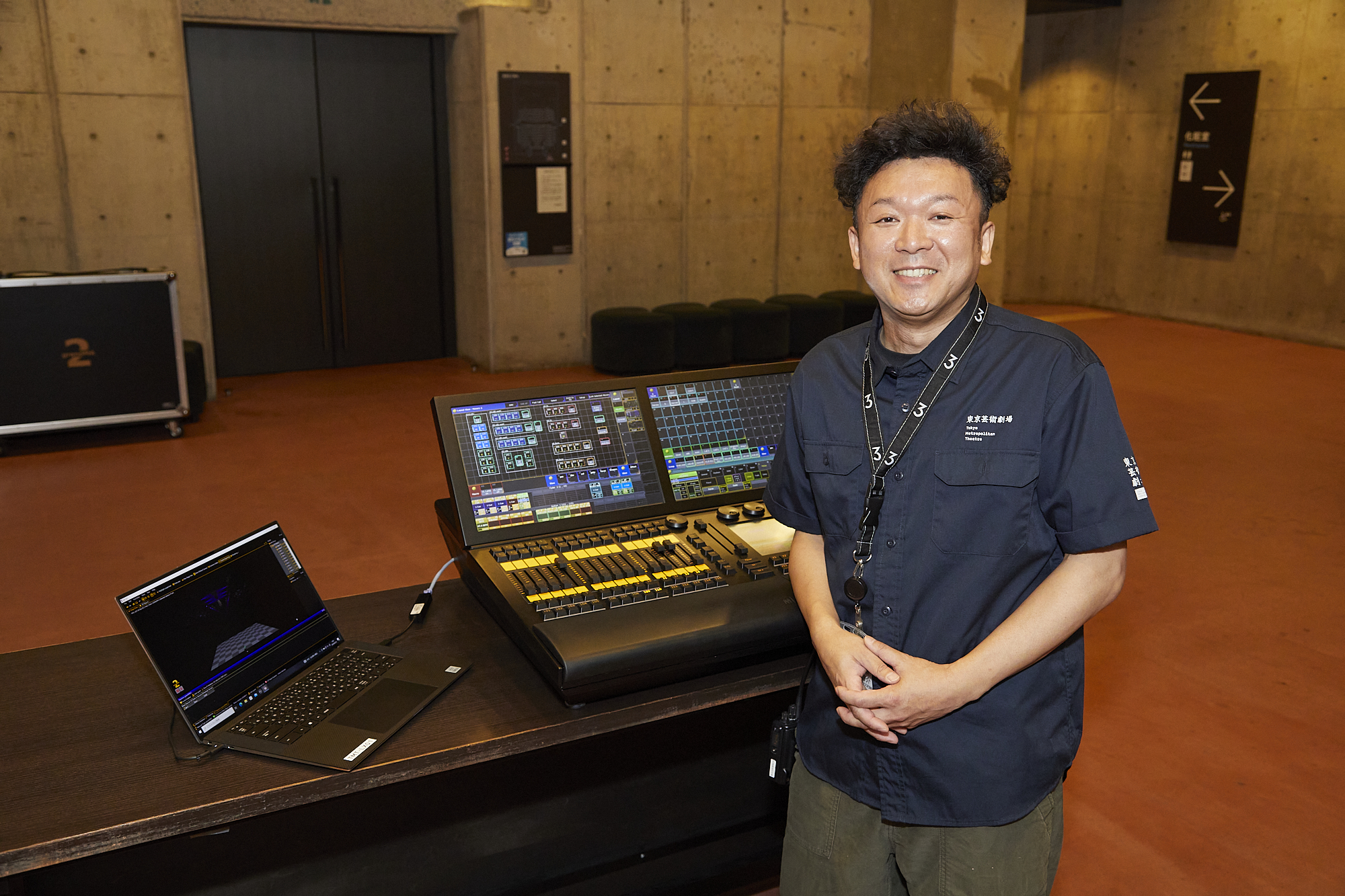

Keisuke Niijima: Bringing joy to audiences through lighting and image projection

“I think most people working backstage fundamentally want to make others happy.” says Keisuke Niijima, who is in charge of the design and programming through lighting and image projection, as well as coordinating stage lighting. He plans lighting effects according to the music and theatre programs and manages both the production and live performance operations. Although his interest lay in sound engineering in high school, he encountered a lighting designer while working part-time on a tour during his vocational school years, which led him into the world of lighting. Initially, he worked for a stage production company, which handled lighting for artists’ concert tours and stage lighting at theme parks. A turning point came with Cirque du Soleil, where he was entrusted with managing lighting, including the operation and management of the team and the operation during the performances. He was impressed to learn that even world-class shows are created by originality and ingenuity of analog techniques. Niijima joined Geigeki in 2012.

Geigeki holds Tokyo’s high school student drama festival annually. “It’s actually more challenging than working with professionals,” says Niijima.

“I try to understand what the students want to do as thoroughly as possible. For example, they may want a gray background, but you can’t make lights gray, so we figure out how to achieve that. I enjoy the process.”

There are three lighting staff members at Geigeki. Niijima says, “Our work can’t be done by one person alone. Each of us has unique qualities, and they can all contribute to what we do.”

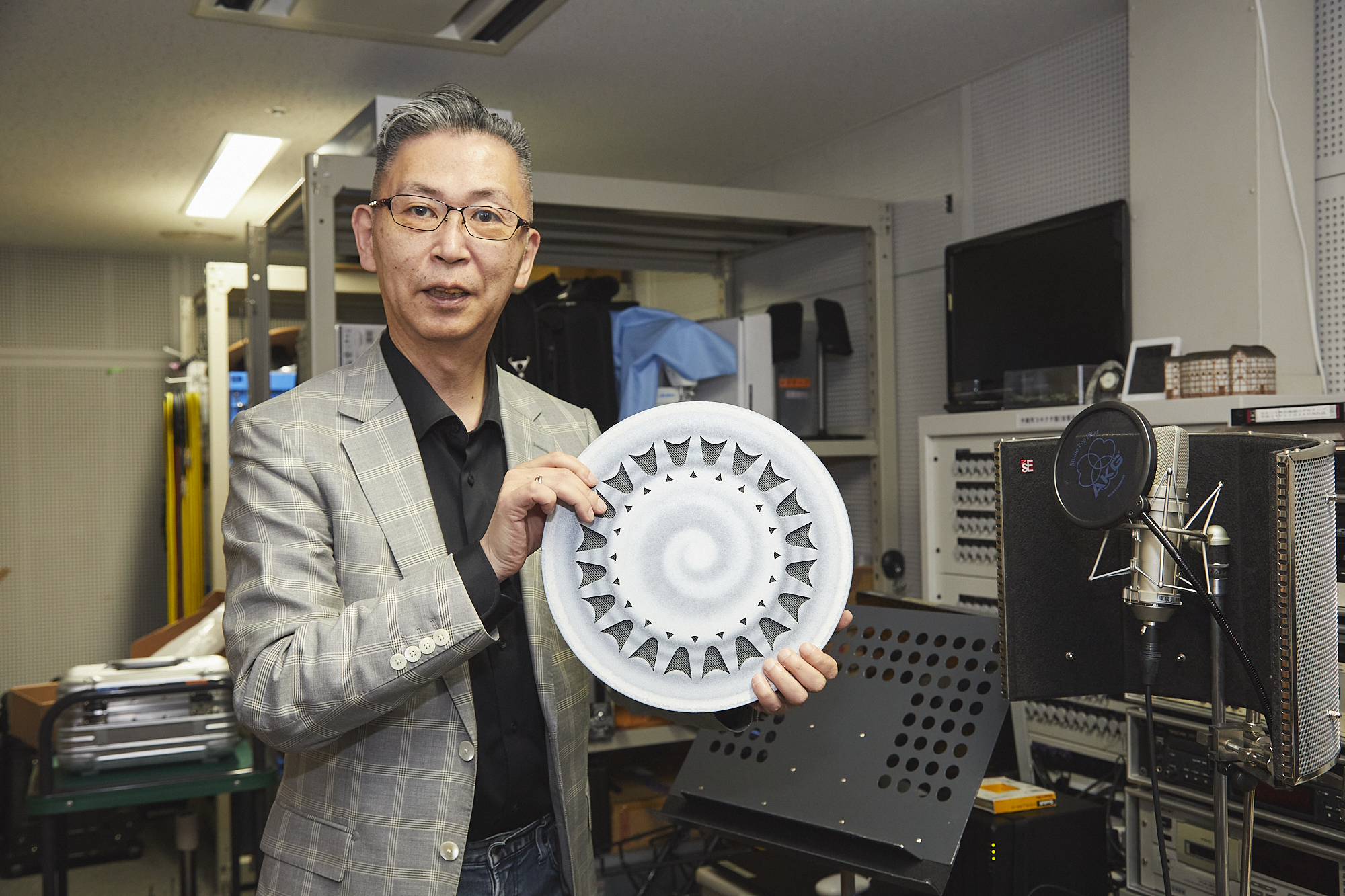

Koichi Ishimaru: Audience-first sound engineering

Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre Opera vol.15: Ikuma Dan Opera “YUZURU,” directed by Toshiki Okada (October 2021).

Currently, two staff members manage four halls. According to Ishimaru, if lighting engineering is about visual direction, then sound engineering is about “auditory direction.”

“Vision is often associated with conscious perception, while hearing is linked to unconscious perception. In theatre productions, visual direction creates the work’s ambience, whereas auditory direction approaches it from the outside to guide the audience into the fictional world unfolded on stage. For example, if a small four-tatami-mat room is built on the stage, and you hear clickety-clack, you know ‘the house is adjacent to a railway.’ If you hear the chug sound from a ship horn, you understand ‘the house is located in a port town.’”

In his work, the audience is the priority. He says, “Sound is a vibration of the air, which can affect a human body. It’s crucial to prioritize the audience in front of us, rather than the director, lead actors, or sponsors. I believe this is the most important perspective in my line of work.”

Chihiro Matsushima: Workplace where differences are respected

Matsushima’s area of responsibility is “stage,” which includes stage design elements like stage sets and props, as well as overseeing the operation and management during performances. Her role, which involves coordinating staff and managing progress while considering the director’s intentions, is also called stage manager. As a child, Matsushima dreamed of becoming a circus clown. However, she was deeply impressed by the play Flowers for Algernon, which she saw with her family by chance, and decided to pursue acting. She went on to study performing arts at university, where she gained practical experience in acting, lighting, set design, and stage management.

There are three staff members responsible for stage management, including Matsushima. She describes the work environment as open, where “I can discuss even trivial matters with the team members, regardless of age or gender. I can express my opinions to my superiors, and the team respects each of our ideas.” Matsushima finds management work, which requires flexibility, “enjoyable.”

“Each performance has different requirements, such as lighting setups, sound plan, and stage sets, so the schedule varies each time. I may compose a schedule in one way, but others’ schedules may be different. There are countless ways, and that’s what makes the job interesting.”