“Cultural Future Camp: Co-creating New Cultural Experiences through Inclusive Design” is a program that was jointly organized by the Creative Well Project (renamed Creative Well-being Tokyo in FY 2022), which has been run by the Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture since 2021, and the Tsukuba University of Technology, Japan’s only institution for the higher education of hearing or visually impaired persons.

![]()

![]()

事務局からのお知らせ

”Cultural Future Camp: Co-creating New Cultural Experiences through Inclusive Design” Report on the Intensive Four-day Workshop [Part 1]

Held over a four-month period from November 2021 to February 2022, the program consisted of three open lectures and an intensive short-term workshop on the theme of information accessibility in the arts and culture. Both incorporated inclusive design, a design method that encourages the involvement of people with disabilities.

This report provides a glimpse of the intensive short-term workshop, which brought together participants of various backgrounds to co-create new ways of enjoying the arts and culture.

*Summaries of all three open lectures are included in the Cultural Future Camp: Co-creating New Cultural Experiences through Inclusive Design report. (Japanese only)

An intensive short-term workshop for co-creating new ways of enjoying the arts and culture

The intensive short-term workshop spanned a four-day period from February 17 to 20, 2022, and was held in the Edo-Tokyo Museum conference room. On the final day of the workshop, participants presented their results online. A diverse range of people participated—students, cultural facility staff, artists, designers, actors, musicians, and researchers—including those with hearing and/or visual disabilities. Participants were divided into four teams, each with its own theme, to conduct workshops and group work led by the diverse lineup of cultural facility staff, artists, and researchers who served as lecturers and facilitators.

Two concepts were key to this program. One was the concept of inclusive design. In order to determine what is most desirable from the perspective of people with disabilities, especially given the wide range of disabilities that exist, this approach brings people with disabilities (lead users) into the design process and encourages their involvement in creating the product or solution together. The other was speculative design, a way of thinking that opens up the mind to new ideas. Participants learned about this method of breaking down stereotypes and coming up with ideas of future possibilities in a lecture, then tried it out in a group work session.

Group work by four teams who co-created ideas, then presented their results

The second half of the workshop (days three and four) began with lectures and group work based on four different themes: Subtitles, Techtile (technology based tactile design), Games, and Music (instrument interfaces).

First, artists and researchers representing each theme gave lectures on their respective activities and ideas. Then the participants split into four teams. Each team included at least one participant with a disability, and the members worked together to co-create their own ideas under the guidance of lecturers and facilitators.

Below, each team will be introduced one by one, including a summary of their group work and their final presentation.

The Subtitles team translated music into colors

Artist Saori Kobayashi led the subtitles team. She presented her musical score drawings, which are her attempts to visualize music by drawing the scenes that come to mind while listening to a song on blank sheet music. Kobayashi has created “pictorial subtitles” for Uta no Hajimari (2020), a documentary film about the Deaf photographer Harumichi Saito, by painting images conjured by the sounds and music played in the film.

During group work, the team focused on differences in the way each person perceives sounds and developed new subtitles based on the theme of “visualizing sound.” Specifically, the members imagined how Deaf team member Katsuhiro Nishioka, who is the representative of the Art and Sign Language Project and a designer at Tanseisha Co., Ltd., experiences music. They decided to proceed while contemplating how they could get him to feel music the way they did.

Members drew pictures in their sketchbooks while listening to sounds produced by a variety of unusual instruments that Kobayashi had brought to the workshop. This activity revealed that regardless of who could hear and who could not, each person expressed the same sound in a different form. While listening to the same sound, some people said that they felt fear and rejection, while others said that they felt warmth.

For example, when listening to sounds that played from left to right, some people felt a wind chime-like resonance or a wave-like echo. On the other hand, Nishioka, who could not experience the sounds without touching the instrument, felt them as plucked sounds because the vibrations stopped when he touched the instrument. Another observation was that Nishioka drew with only one color, while many of the team members used a variety of colors. When he asked them how they chose their colors, they realized that they were doing so unconsciously based on the sounds they heard.

The team also discussed how sounds, such as the sounds of household chores being performed in another room, can be tied to memories or trigger certain emotions.

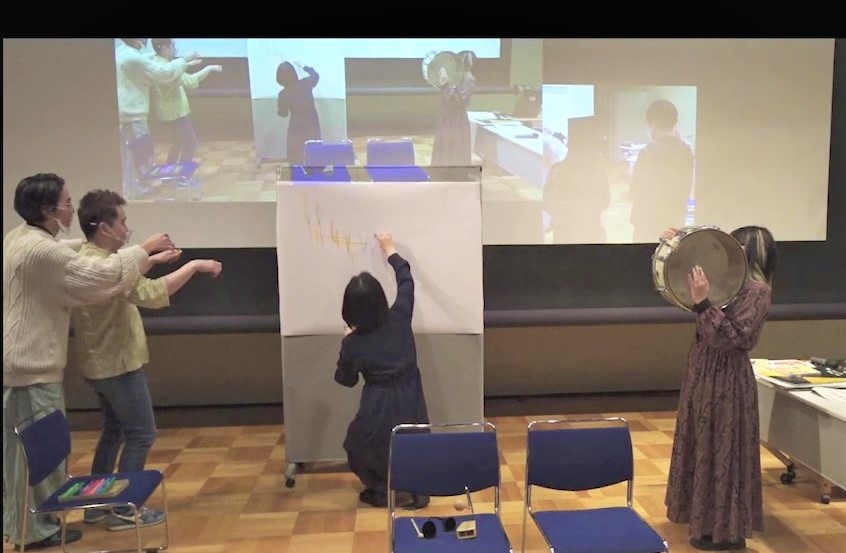

For their final presentation, all members of the team collaborated to create an impromptu drawing of the sounds they felt on a large piece of paper, taking turns drawing while Saori Kobayashi used various instruments to create sounds. Among them was actor Ryusuke Kobayashi, who served as an interpreter, expressing the sounds he heard with his body and conveying them to Nishioka. Ryusuke Kobayashi’s takeaway from the presentation was: “I was able to deepen my awareness of how to perceive and express sounds with all five senses, which gave rise to many new sensations.”

Nishioka seems to perceive sound with his eyes and feel it with his skin. Over these two days, however, his outlook seems to have changed: “I had no experience of representing sound in pictures, so I never thought to translate sound into images,” he said. “I realized that since each person’s picture came out different, each person also had their own way of perceiving sounds. After this experience, I find sounds to be rich and interesting, as though my black-and-white world is changing into a colorful world.”

Following the subtitles team’s presentation, Junichi Kanebako, lecturer of the instrument interfaces team, commented, “There is value in the process of sharing things that are not expressed in language.” If we consider the fundamental question of what sound is, it seems likely that new “subtitles” expressing sound in various forms will be created.

The Games team created a game with one-of-a-kind rules

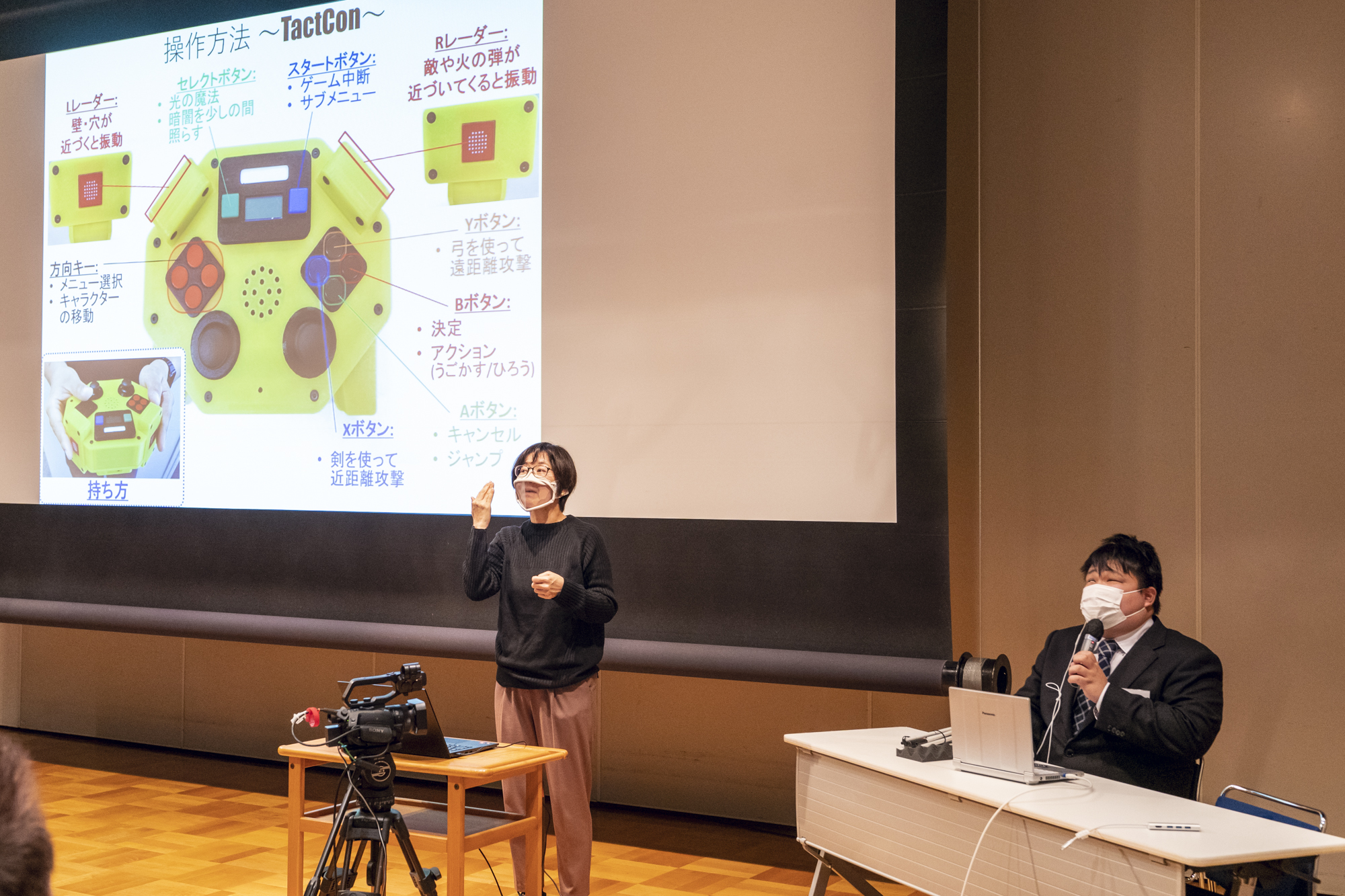

Masaki Matsuo, post-doctoral fellow at the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, was the lecturer for the games team. He is a totally blind game developer who develops audio games for people with visual disabilities that can be played by listening to sounds, and inclusive games that can be enjoyed regardless of disability.

Group work began with the members actually playing games developed by Matsuo, such as Dreamy Train, a train simulator for people with visual disabilities in which players are required to operate a train using only sounds.

Game designer Hiroshi Inukai also led the team as a facilitator. Inukai asked the members, “What is a ‘game’ in the first place?” After discussing various aspects of games, rather than writing code for a computer game, the team decided to develop a simple game in which players move their bodies.

The team then created a new game called “Denshin Game” (movement transmission game) that everyone could play together regardless of their visual and hearing abilities, using a rope and their sense of touch. In the process of creating the game, they aimed to 1) create rules based on each team member’s ideas, 2) have people with hearing and/or visual disabilities from other teams participate in the development of the game, and 3) make varying levels of difficulty so that the game can be adjusted to allow players of all levels to enjoy it.

While trying it out over and over again, the team created rules such as tapping the next person’s shoulder after finishing the movements, raising both hands when everyone finishes, calling out by number, and moving the rope together with players with visual disabilities when checking the movements to see if the team produced the right answer.

Hiromi Nishiura, who is researching devices to facilitate communication between Deaf and hearing people in graduate school, said, “By working together with Masaki Matsuo, one-of-a-kind rules came into being.”

For their final presentation, Atsushi Mori, a deaf-blind member of another team, joined the team members in demonstrating their game. The players formed a circle while holding the rope, closed their eyes, and chose a leader. The leader thought of a pattern of movement and performed it, then tapped the shoulder of the player to the right when finished. This player, in turn, repeated the movements and tapped the next player’s shoulder until the movements were transmitted to the last player. The leader then checked the last player’s movements to see if they were transmitted accurately. During the presentation, they transmitted the motion of raising, then lowering the rope, and were successful for the first time. This created a sense of unity among the participants.

Matsuo was enthusiastic about the results, saying, “When we were playing the game and the rope I was holding moved, and I felt that the person next to me was communicating something by moving their body. Normally, I talk with people around me by relying mainly on their voices, without understanding their gestures or facial expressions. This game gave me the feeling that my senses had expanded, as though I had eyes as well. This could be a clue for new communication tools.”

Reporting and text: Yuri Shirasaka

Photography (starred [★] photos only): Motoi Sato

Translation: Jena Hayama