![]()

![]()

事務局からのお知らせ

People are far more diverse than we imagine

At the international conference on July 3, Li Kotomi raised the question, “It’s easy to say that we will promote diversity, but in reality, diversity is an extremely difficult thing to achieve. Still, what can we do?” Her answer: “We have to start by accepting the fact that human diversity extends far beyond our imaginations.”

Li People living in Japan are relatively familiar with Japanese culture, East Asian culture, and the culture of the West, but they may not be so imaginative when it comes to other cultural spheres. Therefore, we must begin by assuming that humans are fundamentally ignorant and that we are not designed to accept all kinds of differences from the outset.

Human cultures, traditions, and customs are many and diverse. For example, the wearing of veils such as the burqa and niqab by women who follow Islam has at times sparked controversy in the West, as it is seen as a form of female discrimination. In Africa, there is a custom of men whipping women, and some ethnic groups and regions practice ceremonial female circumcision. Where exactly the line between “culture” and “discrimination” should be drawn with respect to the religion, traditions, and customs of a country or region is an extremely difficult question.

And where do we draw the line between “diversity,” “disorder,” and “crime”? As you know, same-sex attraction was considered to be a mental illness until only three or four decades ago, as was gender dysphoria until about a decade ago, but these are no longer the case. We must first understand that the definitions, boundaries, and lines demarcating what is a disorder from what is not, what is a crime from what is not, always differ from era to era and from culture to culture. What matters is who has the power to draw those boundaries, to decide what is criminal behavior or not.

Another tricky thing is the “political correctness” movement, which aims to replace terms that are considered discriminatory with politically correct or neutral terms, while avoiding the use of discriminatory terms as much as possible. While this is certainly the right thing to do, the question of how far we must go with this is more difficult than it seems, because our notions of what is normal and what is not change with the times.

Looking back on the history of the feminist movement, it has been mainly middle-class white women who have dominated efforts to push for equal rights, while black women, sex workers, lesbians, transgender women, and others have not been given the same visibility. Nowadays, the concept of “intersectionality” has emerged. The argument is that there are many kinds of women and that we need to take a closer look at each of their problems and differences.

Thus, movements to respect diversity, eliminate discrimination, and restore rights invariably have their limitations. Our imaginations are limited, and there will cultural spheres that are invisible to us. It’s very difficult to imagine the lives and customs of people who live beyond the boundaries of our imaginations.

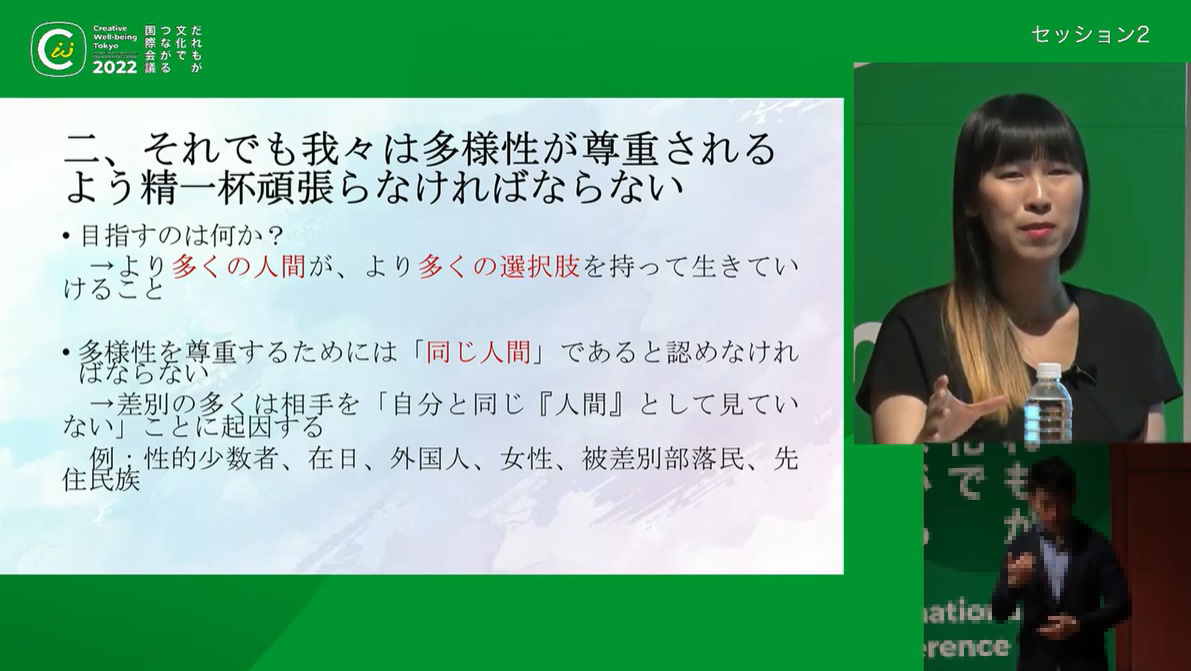

What are we aiming to achieve?

“Still,” Li continued, “We must do our best to ensure that diversity is respected.”

Li The most important thing is for more people to be able to live with more choices than they currently have. It’s impossible for all people to live with all choices available to them, but I think we can strive to offer more choices than presently available.

To do this, we need to cultivate the ability to imagine others. Discrimination often stems from not seeing the other person as a “human being” like yourself. It is vital that we imagine others as “human beings” who have emotions, intelligence, and who can be hurt just like ourselves.

How can we cultivate our ability to imagine others? I believe that creative works can play a key role in this process. Although we inevitably must live our lives in a limited space and for a limited time, we can imagine other people’s lives, other people’s suffering, and other people’s problems through exposure to creative works—novels, films, anime, and TV dramas, for example.

The main objective of respecting diversity is to achieve a society in which everyone can live more freely. It’s not an “all-or-nothing” movement or a “zero-sum game.” It’s not enough to simply engage in dialogue or promote understanding. We must engage in dialogue and promote understanding with the goal of transforming attitudes and systems.

Art is effective in cultivating the imagination to understand others

── Earlier at the international conference, you made the point that while it is impossible to accept all differences, it is possible to aim for a world that respects as many differences as possible. The novels that you write also present a similar narrative. How do you create these stories?

Ultimately, it comes down to experience and observation. Transforming my own experiences and depicting them in another form, while deepening my observations of the people around me and the world I see, helps me to create the worlds in my novels. Also important is valuing the feeling of “discomfort.” I believe that everyone occasionally feels some kind of discomfort with other people, society, or with the world at large. In my case, when those occasions arise, it becomes the impetus for creating a new piece of work. For example, in my novel “Sei wo Iwau” (Celebrate Life, 2021), I explored the sense of discomfort we feel about having been born without our consent.

There’s more than one way to express “discomfort.” I just happen to have chosen the medium of the novel. Other modes of expression—such as music, or painting, or film—could be equally effective, but I can’t do those things. I write novels because I love words, and literature is the mode of expression in which I feel the most comfortable.

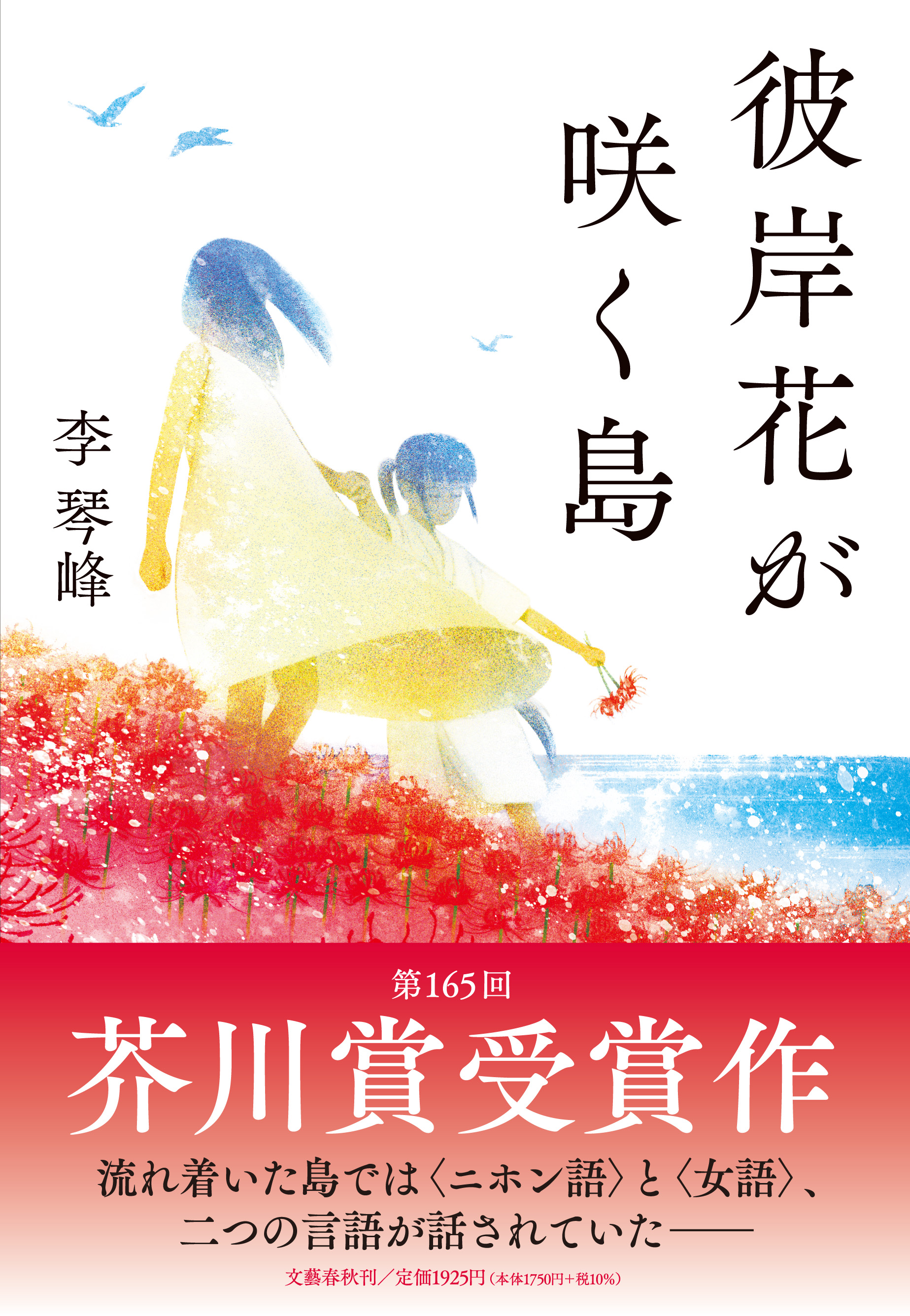

── Your novel “Higanbana ga Saku Shima” is set on a fictional island where three languages coexist: two languages, “Nihon-go” and “Jogo” (women’s language) are spoken natively on the island, while a girl from outside the island introduces “Hinomoto Kotoba”. How did you come up with these new forms of linguistic expression and each of their unique features?

“Higanbana ga saku shima” is a work of linguistic experimentation. I wanted to explore what would happen if Japanese and Chinese were fused together to create a single creole language. Literature, unlike film, does not have sounds. This is significant because languages typically develop as a spoken language first, followed by the written word. If a Japanese-Chinese creole were to be created, it would probably contain sounds that could not be expressed through Japanese characters alone. Novels, however, are limited to expression within the framework of the written word, and I experimented within this framework. Although readers who can only read Japanese will not understand 100 percent of the dialogue, they will still be able to understand the gist of it. They can look at the Chinese characters and intuit the meaning, and that’s all they need to know. I translated this novel into Chinese, and it was really difficult. Normally, translations can take years to be published. Since this work had won the Akutagawa Prize, I was told to hurry up, and I managed it in a year’s time.

── In this novel, the rulers of the island are led by women called “Noro”. Men are not allowed to become “Noro”. Is this an inversion of perspective?

I have always thought that it’s not enough to simply invert gendered positions. There are novels in science fiction that invert the position of men and women, but I wanted to do something different. In “Higanbana ga Saku Shima”, people have used the lessons they learned from history to make life on the island better than it was in the past, yet there are still people suffering due to exclusion. I believe the novel raises the open-ended question, “What should we do then?”

── What is necessary to achieve diversity?

Readers often tell me that they “empathized” with my work. Empathy is important, but I believe it’s not enough on its own. What people empathize with is still those who are the closest to them. If we place all value on empathy, we end up mass-producing content that the majority can relate to. Then it becomes tyranny of the majority. Besides, this fails to serve the purpose of diversity, which is to be exposed to others who are different from yourself. Placing all value on having empathy for forms of expression that are most relatable to yourself will only lead to the mass production of existing values.

The power of empathy is also what creates divisions, such as that of victim and perpetrator. When people empathize with one side because it is more familiar to them, the other side becomes their enemy. Having the “feeling” of empathy, or emotion, is not enough; we need the “logic” of understanding, rationality, and knowledge. We must think rationally about what the problem is in the first place. If we act from our emotions, we will inevitably be divided into “this side” and “that side.” That’s why I think it’s necessary to go one step further than empathy, in order to imagine and understand different things.

Democratic countries operate under a voting system, meaning that they are social systems in which the majority tends to hold more power. Naturally, this has the detrimental effect of excluding the voices of the minority. Because of this, I believe we must listen more carefully to the voices of the minority.

Take foreigners, for example. There are many foreigners all around us in Japan, supporting the country as convenience store employees, technical interns, and so on. I think we need to do something to address this situation where they are in fact all around us but hardly perceived as visible and rarely appear in forms of artistic or literary expression. This is true not only for foreigners but also for LGBT individuals. It’s frustrating that although everyone must have some friend or acquaintance who is LGBT, their presence is not readily acknowledged, and it’s difficult for them to make a difference in society. For me, literature and art are enjoyable, of course, but I also believe I have an artistic mission to bring a voice to these people.

Interview by Yuri Shirasaka

Edited by the Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture

Translated by Jena Hayama